A Plan for Economic Security in an AI Future

mmills@economic-security.ai

Fall 2025

Overview

If we experience mass job loss from AI, incomes will plummet and many people will struggle to meet basic needs. Massive income loss will also be felt in the government due to corresponding loss of income and payroll taxes. At the same time that these losses are occurring, corporations may be exploding in value precisely because they have replaced humans with AI and robots.

To prepare for this possible future, we propose the use of an index to track job disruption that can be used to trigger a tax on corporate equity, expanding on an idea proposed by Sam Altman in 2021. The use of a conditional trigger allows policymakers to put a plan in place today with the assurance that the tax would only be enabled in the event of a Great Depression-level crisis.

Why We Need a Plan

-

If AI succeeds it could cause massive job loss and lower wages. Millions of Americans would struggle to meet basic needs, and our current social safety net would collapse.

-

84% of federal government revenue comes from personal income taxes and payroll taxes. This critical source of tax revenue would quickly erode due to lost jobs and lower wages.

-

Social Security and Medicare (primarily funded by personal income taxes and payroll taxes) would be massively disrupted. The ability for the government to pay for standard government functions (defense, infrastructure, etc) would also be at risk.

-

Airplanes have life vests not because there is a high probability that they will have to land in water. They have life vests for the low probability (but extreme situation) that they are needed, and can help people stay above water.

-

We should hope for the best, but we can prepare for the worst. America currently has no life vest for the potential scenario of mass job loss due to AI and robotics.

Paying For the Plan

-

At the same time that human labor hits a crisis, businesses may be exploding in value and achieving record profitability. Implementing a new corporate tax is perhaps the best candidate to replace potential lost tax revenue and meet the needs of society.

-

In 2021, before ChatGPT debuted, Sam Altman proposed an idea for taxing corporate equity as a way to fund a future society where human jobs are severely disrupted.

-

Altman stressed that the tax should be on company shares rather than profits because profits can be gamed, and a tax payable in company shares (or cash equivalent) “will align incentives between companies, investors, and citizens.”

-

A tax on equity may also be necessary to ensure a large enough base. As people lose their incomes and have their wages lowered, that loss is felt twice: once at the personal level (loss of income) and a second time at the government level (loss of income tax).

-

A corporate equity tax is great in theory, but it’s hard to imagine politicians and CEOs considering it when it’s not needed. Altman suggested starting small with the tax today. We propose a conditional trigger to enable the tax only if we ever need it in the future.

Using a Conditional Trigger

-

A conditional trigger allows us to put a tax on corporate equity in place, but enable the tax only in the event of a true crisis (i.e. a pre-defined trigger is met). Similar to a life vest on an airplane, we can create a tax that is intended to be used only in case of emergency.

-

If we never experience a crisis, the tax is never enabled. This premise is what differentiates this plan from other approaches: the tax is conditional — it takes effect only in a crisis.

-

Creating a tax that is conditional on job disruption also means that if we experience temporary disruption but ultimately find new jobs (as we have in previous technological revolutions) the tax would eventually be disabled.

-

If we set a high threshold for enabling the tax, we can reflect an ideology to not interfere with the free market or disrupt the status quo unless a true crisis has emerged.

-

Conceptually, we can think of an appropriately extreme trigger as: levels of job disruption not seen since the Great Depression, lasting for 6 months in a row.

Calculating Job Disruption

-

In order to trigger the tax, we need to come up with a method to calculate job disruption so we can define what is a healthy baseline and what is an extreme crisis.

-

AI and robots may replace human workers outright leading to unemployment (this is generally the most commonly discussed concern today).

-

AI and robots may also expand the supply of labor such that demand for human hours or skills is reduced (such a reduction is what is meant by the term “underemployment”).

-

Competition with AI and robots could also lead to wage loss (even if people are still technically employed). Simply having a job may not prevent a crisis if competition with AI drives human wages below subsistence level, as some have suggested.

-

We want an index that can track all of these key indicators of job disruption to ensure we are prepared for a variety of possible futures. Put simply:

Job Disruption = Unemployment + Underemployment + Wage Loss

Tracking Unemployment

-

When the media mentions unemployment numbers, they are referring to a metric called U-3, but U-3 captures only unemployed people that have actively looked for work in the past four weeks. In an AI future, people may simply stop looking for work altogether.

-

If we instead look at the Employment-Population Ratio for prime age adults (PA-EPOP), we can get a better understanding of how many working-age (25-54 years old) adults are actually employed (this age range roughly attempts to remove students and retirees).

-

PA-EPOP has been consistently around 80% for the past 30 years or so with clear drawdowns during the financial crisis and the pandemic.

-

Because PA-EPOP represents the percentage of employment, we can subtract it from 100 to give us total unemployment of working-age adults.

(100 – PA-EPOP)

Unemployment

Tracking Underemployment

-

Underemployment effectively means that people are employed, but they wish they had more hours or work that more closely meets their skills or education level. To track underemployment we can leverage an alternate unemployment metric called U-6.

-

U-6 includes those officially unemployed (U-3), those who want a job but have recently stopped looking for work (people considered “marginally attached” to the labor force), and people who are employed part time for economic reasons.

-

Part time for economic reasons effectively means people that want to be working full time, but are only able to find part time work due to economic reasons such as unfavorable business conditions or seasonal declines in demand for certain jobs.

-

If we subtract U-3 from U-6, we’re primarily left with people employed but who wish they had more hours — a rough proxy for underemployment.

(U-6 – U-3)

Underemployment

Tracking Wage Loss

-

Wage Loss essentially means that wages are not keeping up with inflation. If wages don’t keep up with inflation, employment numbers can look healthy, but people may have trouble affording essential needs such as groceries, healthcare, and housing.

-

We can use the Wage Growth Tracker (WGT) from The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to compare wages vs. inflation.

-

Wage loss occurs if wage growth is lower than inflation, so we can subtract WGT from CPI to track wage loss (CPI — WGT). Wage loss affects only those who are employed, so we multiply this difference by the percentage of prime-age employed (PA-EPOP/100).

-

Because wage loss is measured relative to inflation, changes are more subtle. As a result, we double the Wage Loss term in the index, effectively equating a 1-point change in wages relative to inflation with a 2-point change in Unemployment or Underemployment.

2(CPI – WGT)(PA-EPOP/100)

Wage Loss

The Job Disruption Index

-

Taken together, the elements above give us a Job Disruption Index (JDI):

JDI = (100 – PA-EPOP) + (U-6 – U-3) + 2(CPI – WGT)(PA-EPOP/100)

Unemployment Underemployment Wage Loss

JDI = (100 – PA-EPOP) + (U-6 – U-3)

+ 2(CPI – WGT)(PA-EPOP/100)

Unemployment + Underemployment

+ Wage Loss

-

We specifically use publicly available, historical, and familiar economic indicators in order to facilitate discussion among policymakers, economists, business leaders, and the general public — a final index may be more complex.

-

Marginally attached workers are double counted, but the effect on the directional nature of the index is minimal.

Defining a Crisis

-

We can define a healthy baseline for the Job Disruption Index at 22 based on historical trends (PA-EPOP at 80, U-6 at 7, U-3 at 4, and CPI – WGT at -1).

-

We estimate that JDI would have peaked at 35 in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and would have nearly reached 30 during the pandemic before quickly recovering.

-

We want to ensure that the tax is not enabled as a result of standard market cycles (including recessions) or a sudden, brief event like a market crash or another pandemic. So, we want a trigger that is both extreme in degree, as well as sustained in duration.

-

We can define a crisis that is both extreme and sustained as JDI higher than 37 for six consecutive months — this would be the trigger to enable the tax.

-

While the threshold to enable the tax is high, a lower threshold (e.g. JDI = 33) to disable the tax could ensure the tax is not continually enabled and disabled.

Calculating the Tax

-

We can create a tax rate that scales with the severity of the crisis by linking the tax rate directly to the Job Disruption Index. Larger crisis = larger tax = larger revenue.

-

If JDI reaches 37, we can say that it has increased 15 “Crisis Points” (CP) from the baseline of 22. We can multiply these Crisis Points by a fixed percent to determine a quarterly tax rate. For illustration purposes, we use 0.01%, giving us a quarterly tax rate of 0.15%.

Quarterly tax rate = Crisis Points x Percent

Quarterly tax rate = 15 x 0.01% = 0.15%

-

If job disruption continues to increase, the tax rate will increase in direct proportion to the level of the crisis. Unlike previous economic crises, job disruption may simply continue to get worse over time.

-

The tax could be capped at 0.49% quarterly (less than 2% annually). A hard cap could serve to prevent excessive tax rates from stifling the growth of companies.

Collecting and Distributing Revenue

-

The plan could establish an “Economic Security Fund” (ESF) to collect and distribute tax revenue if the trigger is met. The Fund could be managed by an independent commission (not elected officials) much like the Federal Reserve.

-

The Fund could have a dual mandate to provide economic security for the government through revenue shortfall support and for people in need by way of “Economic Security Payments” (ESP).

-

Economic Security Payments could be a more targeted form of Universal Basic Income (UBI), potentially limited to individuals with incomes (or net worth) under a certain amount, or scaled according to need.

-

If the trigger is met, the tax is enabled and companies send the required shares (or the corresponding U.S. dollar amount) to the Fund on a quarterly basis. The Fund could then sell 100% of any shares for U.S. dollars in order to efficiently distribute the revenue.

-

Automated revenue sharing could allow tax revenue to be immediately distributed to the government and people in need, preventing delays and reducing administrative burden.

What the Plan Could Deliver

-

We model increasing unemployment over time to test the resilience of the plan in an extreme scenario: 70% of working-age adults do not have a job by 2050.

-

With a revenue split of 60% for U.S. adults, 30% for the government, and 10% for sustainable fund growth, the plan could deliver the following outcomes:

-

Economic Security Payments for each adult = $13,630 annually

-

Federal Government revenues = $1.9 trillion annually

-

The Fund sustainably grows to $10 trillion

-

$13,630 per adult reflects all U.S. adults receiving payments. If payments are limited by need, that amount could increase and allow the system to factor in dependents as well.

-

It’s also possible that $13,630 in 2050 may have more purchasing power if AI causes the price of goods and services to come down due to efficiency gains. In a worst case scenario, this amount can still provide for essential needs.

Model assumptions: 2025 market cap of all companies = $60 trillion, growth = 7% annually; trigger is met in 2032 when total market cap of all companies = $96 trillion. Rate cap of 0.49% on quarterly tax applied. Complete scenario models in Appendix.

Excess Funds

-

As indicated in the scenario above, there could be a substantial sum of money remaining in the Fund. Money that remains allows the Fund to grow over time such that it can provide economic security to future generations of Americans.

-

Excess funds could be used to make up for state and local tax revenue shortfalls, or they could potentially be used to pay down a portion of the national debt.

-

Excess funds could also provide economic security to others outside America. Similar plans to the one proposed here may work for other advanced economies, but many countries simply would not be able to generate sufficient revenue.

-

Even if America is able to successfully manage the transition to an AI future, true economic security might not be felt or achieved if much of the world is in disarray.

Challenges with the Plan

-

It’s a new tax.

No one likes taxes. Corporations particularly don’t like taxes — see the Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich evasion technique. But taxes are a known entity, and this makes them easier to discuss and enable than many alternative mechanisms.

-

Why not just tax only the AI companies?

It’s quite possible that the AI companies are not actually the big winners. If intelligence becomes a commodity, particularly if delivered by highly capable open-source models (e.g. DeepSeek) that can be run locally, intelligence may end up being close to free for many use cases, including replacing human labor.

When the internet was first invented, if we had decided to tax the bandwidth providers only, we would’ve missed the fact that the value of the bandwidth mostly accrued not to those companies, but to the companies that utilized the bandwidth such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook (Meta).

-

It’s applied unfairly to all businesses.

Will a company that makes sausages benefit from AI and robotics? Maybe not as much as a call center company. What if robots make the sausage? What if the meat is grown in a lab that utilizes AI? It’s hard to know who will benefit most, but almost all companies stand to benefit if AI turns out to be similar to electricity or the internet: an indispensable and critical resource for every business in every industry.

-

Why not just use public companies?

If you don’t include private companies, you could have public companies converting to private to avoid the tax. There is also tremendous value in private companies (OpenAI is currently a private company, for example). While it is quite complex to value private companies and their equity, it seems to be a necessary aspect of this plan for viability. Sam Altman provides some ideas on how and why to include private companies.

-

Won’t companies just issue new shares?

It is likely many companies will issue new shares. These new shares will dilute existing shareholders, but will also make it simple for the companies to comply with their tax responsibilities.

-

Companies will leave the U.S. and set up elsewhere to avoid the tax.

This is certainly possible. Incentives could help prevent such repatriation of companies. Disincentives could also be considered — the U.S. currently has an “exit tax” for citizens, for example. It will also help if there is some sense that other advanced countries would eventually adopt a similar plan — something like the Global Minimum Tax from the OECD could work to limit relocation.

-

This plan will reduce the incentive to work.

Possibly. The main purpose of the plan is to underscore that we may not even have a choice to work (for income) in the future.

-

What about meaning and purpose without work?

This plan is focused on providing a framework for economic security (essential needs) so that people have the luxury of thinking about meaning and purpose.

-

This is a waste of the government’s time. AI isn’t going to cause job loss.

Previous technological revolutions have always created more jobs, so why might this time be different? One helpful exercise is to think of AI and robots as “Artificial Labor” rather than Artificial Intelligence. Would Artificial Labor cause humans to lose jobs? Almost by definition it might do exactly that.

-

Why not spend the money on retraining rather than handouts?

Government can choose to spend some of their budget on retraining, just as they currently do. It’s unclear if retraining will work in a world where most human labor could be done better by an AI or a robot. We may still prefer humans as nurses for example, and maybe those are among the jobs that remain for humans to do.

-

Couldn’t this be done with VAT or Land taxes?

Possibly. VAT is not familiar to Americans, so it creates an immediate hurdle to the conversation. It may also be politically challenging to add a VAT when the economy is in crisis. Land taxes (unlike property taxes) are even further removed from public discourse, but all options should be considered. Altman proposed land taxes alongside a corporate equity tax in his 2021 post.

-

Will this replace existing programs?

This plan attempts to fill the revenue gap in government from income and payroll taxes, as well as provide income support for human labor. Some programs may become redundant over time, but the plan is not intended to immediately replace all social welfare programs, unlike some other UBI and tax proposals.

-

BLS data may become politicized.

This recent development is unfortunate, but there is some debate on how much the data can truly be manipulated. Ultimately, if this plan is adopted, the final index could leverage other public and private data sources as a check on the accuracy of BLS data.

If the BLS is a crucial input to the index, it will require appropriate funding and resourcing including better tools and techniques for aggregating data in a highly dynamic economy. Better technology, including the use of AI, could create more accurate BLS data and reduce (or eliminate) revisions to that data in the future as well.

Conclusion

AI could lead to massive disruption in human jobs. The effects on society and the economy could be catastrophic if we don’t put a new system in place today. A tax on corporate equity in an era of explosive growth is both logical and sustainable — the use of an index-based trigger makes it politically possible.

Utilizing a strict, pre-defined trigger to enable the tax only in the event of a true crisis means that it costs us almost nothing to put this plan in place today, while the cost of having no plan at all could be truly astronomical for America.

The future of work is highly uncertain. We should have a plan.

Research Informing This Plan

Alternative Proposals

Moore’s Law for Everything Sam Altman

Here’s How To Share AI’s Future Wealth Saffron Huang, Sam Manning

Addressing the U.S. Labor Market Impacts of Advanced AI Sam Manning

Designing an AI Bond for Growth and Shared Prosperity in the UK Emma Casey, Helena Roy, Emma Rockall

The Windfall Clause: Distributing the Benefits of AI for the Common Good Cullen O’Keefe, Peter Cihon, Ben Garfinkel, Carrick Flynn, Jade Leung, Allan Dafoe

Taxing Artificial Intelligences Julian Arndts, Kalle Kappner

Broadening the Gains from Generative AI: The Role of Fiscal Policies Fernanda Brollo, Era Dabla-Norris, Ruud de Mooij, Daniel Garcia-Macia, Tibor Hanappi, Li Liu, Anh D. M. Nguyen

Bill Gates: This is why we should tax robots Kevin J. Delaney

Tax not the robots Robert Seamans

Policy Options for Taxing the Rich Lily L. Batchelder, David Kamin

Tax Reform Alternatives For the 21st Century AICPA

AI and Labor

Preparing for the (Non-Existent?) Future of Work Anton Korinek, Megan Juelfs

AGI could drive wages below subsistence level Matthew Barnett

The Twilight of Labor Brandon Wilson

Capital, AGI, and human ambition Rudolf Laine

AI: Dystopia or Utopia? Vinod Khosla

Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Income Distribution and Unemployment Anton Korinek, Joseph E. Stiglitz

Artificial General Intelligence and the End of Human Employment: The Need to Renegotiate the Social Contract Pascal Stiefenhofer

Forging A New AGI Social Contract Deric Cheng

AI and the Economy

The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance Justin B. Bullock (ed.) and others (ed.)

Explosive Growth From AI Automation: A Review Of The Arguments Ege Erdil, Tamay Besiroglu

The Macroeconomics of Artificial Intelligence Erik Brynjolfsson, Gabriel Unger

Machines of mind: The case for an AI-powered productivity boom Martin Neil Baily, Erik Brynjolfsson, Anton Korinek

Artificial Intelligence, Employment and Income Nils J. Nilsson

Economic Policy Challenges for the Age of AI Anton Korinek

The Economics of Transformative AI Anton Korinek

Scenarios For The Transition To AGI Anton Korinek, Donghyun Suh

Scenario Planning for an A(G)I Future Anton Korinek

Appendix

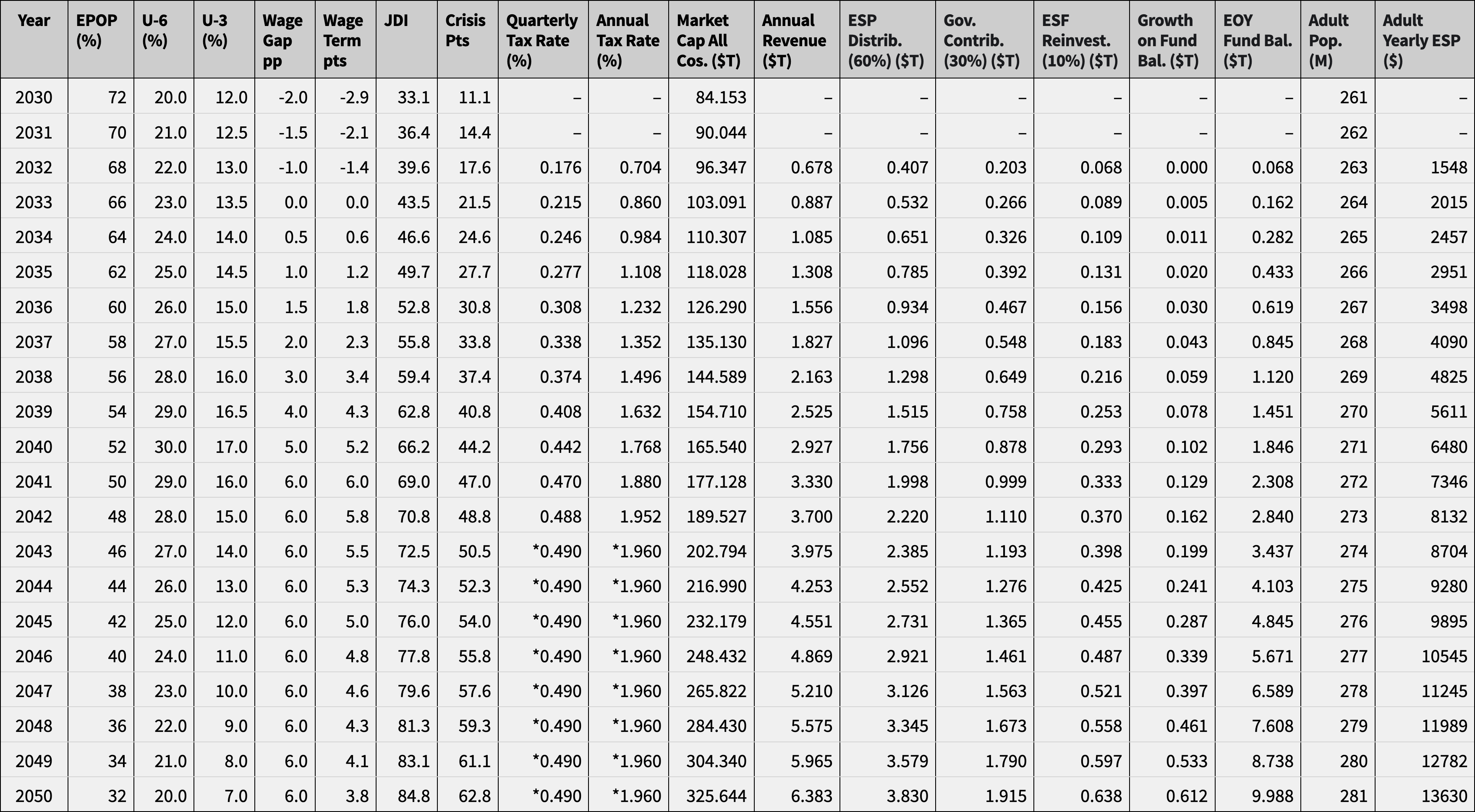

Scenario A: Continuous mass job loss

We model increasing unemployment over time to test the resilience of the plan in an extreme scenario: The trigger is met in 2032 when JDI exceeds 37 for 6 months straight. PA-EPOP declines 2% per year, U-6 and U-3 peak in 2040 and return to a “new normal” of a large number of people no longer in the active labor force. Wages rise initially due to AI enhancement, but then fall and lag 6 percentage points relative to prices.

The quarterly tax is enabled in 2032 at 0.176% of company shares (JDI = 17.6), and companies send these shares (or the corresponding US dollar amount) to the Fund every quarter at the required rate. The Fund sells 100% of any shares for US dollars upon receiving them. 60% of the dollars are distributed to U.S. adults as Economic Security Payments, 30% of the dollars are sent to the government, and the remaining 10% is reinvested into the Fund.

Assumptions: 2025 market cap of all companies = $60 trillion, growth = 7% annually; trigger is met in 2032 when total market cap of all companies = $96 trillion. A rate cap of 0.49% on quarterly tax is applied to assure businesses that taxes won’t exceed 2% annually.

By 2050 with JDI at nearly 85, we model the following outcomes:

-

Economic Security Payments for each adult = $13,630 annually

-

Federal Government revenues = $1.9 trillion annually

-

The Fund sustainably grows to $10 trillion

Scenario A – Continuous mass job loss

* = rate cap is met

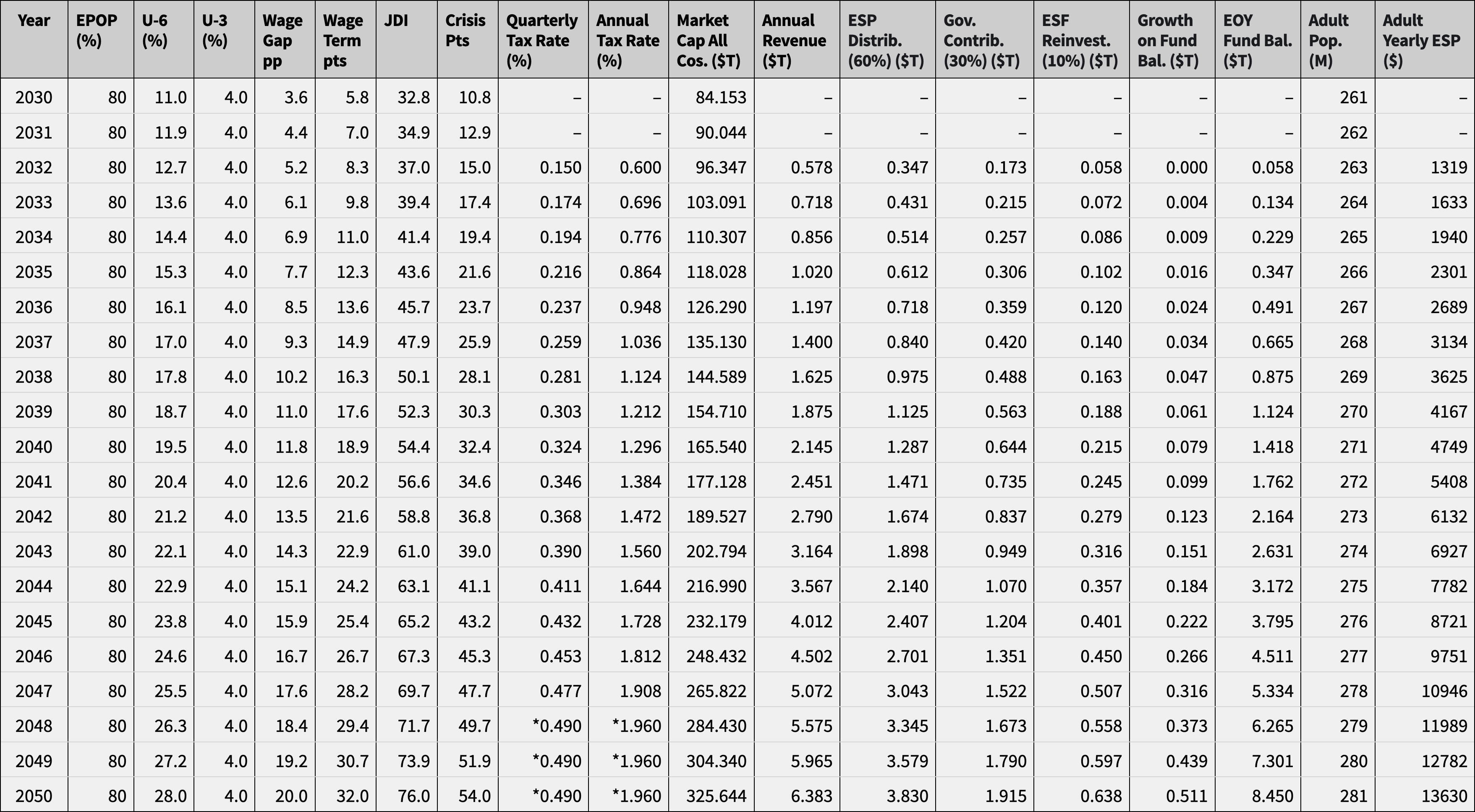

Scenario B: Continuous mass wage loss

We can also imagine a “gigification” future where employment is steady, but wages have dropped (much faster than prices) due to competition with AI and robots. People would still technically be employed, but their wages would have come down significantly.

PA-EPOP at 80 and U-3 at 4 would look healthy, but U-6 might be 28 and the Wage Gap might be 20 percentage points. The Wage Gap measures how much wages are falling behind inflation, or the loss of purchasing power (the Wage Term indicates the weight of Wage Loss as calculated in the index). In this scenario JDI would be 76, indicating a severe wage loss crisis.

2050 outcomes would be similar to Scenario A, with Fund growth slightly lower at $8.5 trillion.

Scenario B – Continuous mass wage loss

* = rate cap is met

The numbers and models presented here are meant to demonstrate the viability of the plan and are not intended to be final. Further refinement and extensive economic modeling will ultimately be necessary.